Common sense is supposed to reign in the law, but so often it doesn’t, especially when the desired pre-conceived outcome disagrees with common sense.

The United States has a little thing called the 6th Amendment:

VI: In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury of the state and district wherein the crime shall have been committed, which district shall have been previously ascertained by law, and to be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation; to be confronted with the witnesses against him; to have compulsory process for obtaining witnesses in his favor, and to have the assistance of counsel for his defense.

Similar protections for due process are also present under the 5th amendment.

A few hundred years of jurisprudence have qualified these rights into certain protections and processes that law enforcement and the courts are required to apply to ensure the constitutional rights of an accused are complied with.

For example: In a police interview, when a suspect requests a lawyer, the interview must end until a lawyer is supplied. If the police continue to question, they have breached the suspect’s rights under the 6th amendment and risk the admissibility of evidence. (Edwards v Arizona)

Sometimes the request is ambiguous and sometimes it isn’t but the Police think that a lawyer may get in the way of a conviction (they’re known for doing that).

This is not what’s up.

Warren Demesme voluntarily agreed to have a chat with the police at an interview down at the station. During the interview, Desmesme realised that he was being questioned as a suspect in the sexual assault of a child and promptly requested a lawyer. Or did he? Kindly parse the following sentence:

“I know that I didn’t do it, so why don’t you just give me a lawyer dawg ‘cause this is not what’s up.

Desmesme sought to have the evidence from the interview excluded at his trial. This was denied and he was convicted based on that evidence. Desmesme appealed on the basis that his 5th and 6th amendment rights were violated. The appeal was denied. Desmesme appealed again, to the Louisiana Supreme Court. The Louisiana Supreme Court denied to take the case but Justice Scott Crichton did pen an opinion explaining the Court’s refusal. The problem apparently originated from the trial court’s transcript, which recorded “lawyer dog” instead of “lawyer dawg“. Crichton J, completely unironically, wrote:

“the defendant’s ambiguous and equivocal reference to a ‘lawyer dog’ does not constitute an invocation of counsel that warrants termination of the interview.”

Perhaps if the transcriber had used a comma, the Louisiana Courts would have recognised asking for a “lawyer, dog” not a “lawyer dog”, whatever that is, but even that’s just unrequired sympathy for Chrichton J’s position. Desmesme was clearly speaking plainly, albeit colloquially, and transcription notwithstanding, there was no real ambiguity to actually resolve. By penning his brain vomit, Crichton J probably created enough reason to have the decision overturned in the US Supreme Court, should they agree to accept the petition.

In Davis v United States, Willie Davis was stopped during a traffic stop and the police found an illegal weapon in the car. Davis requested a lawyer, one wasn’t provided, the interview continued and Davis made incriminating statements. The Supreme Court held that if a suspect’s request:

“is not an unambiguous or unequivocal request for counsel, the officers have no obligation to stop questioning him…[H]e must articulate his desire to have counsel present sufficiently clearly that a reasonable police officer in the circumstances would understand the statement to be a request for an attorney.”

The test is therefore whether a reasonable police officer in the circumstances would have understood the request.

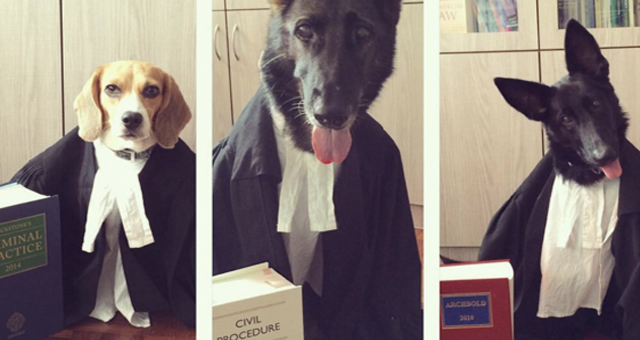

The test of the reasonable person or, in this case, the reasonable police officer can always be manipulated. The Lousiana Supreme Court would probably be better legally placed if they had given no reasons at all instead of diving deep into a diatribe explaining the differences between “lawyer dog” and “lawyer dawg”. But perhaps Demesme should have more clearly articulated who he wanted as his lead counsel…get it? (I almost made it without a single terrible gag).